VEIL DEBATE | HERE AND THERE

Jess McConnell

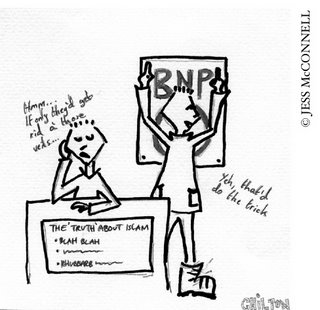

Having mined every last nugget of scandal from the recent crisis surrounding Jack Straw’s comments over the veil, this country as a whole seems in desperate need of a little more understanding and basic knowledge of the subject. The controversy surrounding Mr. Straw’s views was almost purely a media creation, with newspapers eagerly taking his words out of context and busying themselves with creating sensationalist headlines.

All the while, the seeds of an important debate were ignored. Throughout the weeks that followed, print media, television and radio stations devoted unprecedented airtime to the story, yet failed to conduct a sustainable debate, much less produce a single constructive conclusion. Extreme views from both Muslims and non-Muslims made for juicy reporting. While it seemed that every man and his dog were approached for their own two cents’ worth.

This episode proved both worrying and frustrating. The extent of this country’s ignorance and prejudice has been revealed and is truly astounding. Of the countless opinions put forward, almost all were mis- or entirely uninformed. The situation was exacerbated by the fact that hardly a single article or programme gave time to a factual exploration of the history behind the veil or the reality of its position in the Islamic faith today.

This is not to say that we should all be experts or that one must be an expert before discussing the topic. Rather, that the lack of effort in seeking better understanding, instead of provoking a highly-charged and overly subjective debate, was shameful.

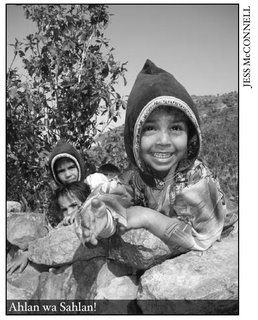

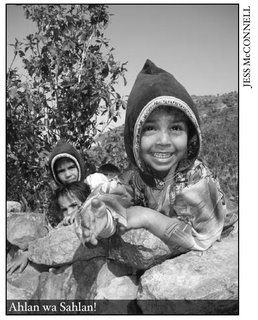

Perhaps this imbalance could be partially addressed by focusing here on a particular country in the Middle East. Yemen is a nation where veil-wearing is as big a part of life as going to work or having breakfast. It is one of the few remaining Islamic states where close to 1oo% of women wear the niqab - the veil covering the whole body except for the eyes. A large proportion of older women wear black gloves as well, and in more isolated rural areas women often cover their eyes with a thin black mesh. While this custom is normal for Yemenis, it is certainly not without controversy of its own. Yemenis, for the most part, are happy to discuss the veil but rarely will two people, male or female, express the same opinion. Reasons for its dominance seem few and far between, with even the most traditional Yemenis often unable to account for its popular resurgence in recent decades.

country in the Middle East. Yemen is a nation where veil-wearing is as big a part of life as going to work or having breakfast. It is one of the few remaining Islamic states where close to 1oo% of women wear the niqab - the veil covering the whole body except for the eyes. A large proportion of older women wear black gloves as well, and in more isolated rural areas women often cover their eyes with a thin black mesh. While this custom is normal for Yemenis, it is certainly not without controversy of its own. Yemenis, for the most part, are happy to discuss the veil but rarely will two people, male or female, express the same opinion. Reasons for its dominance seem few and far between, with even the most traditional Yemenis often unable to account for its popular resurgence in recent decades.

Early last century, the veil was much less prevalent in the country and women often wore no headscarf at all. No doubt the British presence in Aden helped to foster a more liberal and more secular culture, the absence of which, since 197o, is a sign of Yemenis actively reclaiming their Islamic heritage. However, older men and women will occasionally reminisce fondly about times gone by, when there was less of a divide between the sexes, and freely admit that life has since become more difficult. In short, although the niqab is held as an important symbol of modesty and protection for today’s Yemenis, few see it as entirely positive.

Often, when speaking to Yemeni men, a clear divide is detectable between what they say in general terms and any references to their own families. Ideally, yes, the veil would be less of an unresolved issue, but realistically, to abandon it would be unthinkable.

A Yemeni, whom I met while travelling in the country, told me of his experience as he tried to explain the contradictions he encounters in his own life. A religious man, who walks each morning at sunrise to his local mosque and even abstains from the national pastime of chewing the mildly intoxicating qat leaf, he was married recently to a family friend, some years his junior. They drove to Aden together, after a long and strictly traditional wedding ceremony, to spend some time alone, but when my friend suggested his new wife uncover her face in the car, she refused. Motorways do not exist in Yemen, and so their route South took them through quiet, mountain roads and maybe the odd, ramshackle village. In addition, he told me, the temperature in his old land-cruiser was almost stifling, rising even further as they travelled deeper into the desert. The story was told with a look of sadness and at times guilt. This man regards himself as entirely true to his faith and yet he feels he may have insulted his wife without even meaning to. The veil remained and my friend, having lived a traditional Yemeni life for over twenty-five years, was left with a new kind of restriction to deal with, a deeper and more affecting sort of divide.

Communities in Yemen exist within strict social boundaries, which, if crossed, can bring incalculable shame upon an entire family. Although not a small state, extended family groups are usually spread out among small villages all over the countryside. This, the result of the loyal preservation of an ancient tribal system, renders change on any level a monumental occurrence. If one relative living in Sana’a, the capital, begins to draw unusual attention, news will spread down the street, into the local area and before long out into the country, to that family’s home-village and the tribe as a whole. One person alone could not bear such pressure. The Yemeni ‘guilt-culture’ is a powerful concept that limits discussion of progression or reforms to the theoretical. So, despite rational, even regretful, debate, there is simply no room for change.

Another story thrust into the spotlight following Jack Straw’s comments was that of Aishah Azmi, a classroom assistant in West Yorkshire. This young Muslim woman wears the niqab and refused to remove it in front of male staff at the school where she worked. The attitude with which Azmi approached the question of her behaviour is mirrored in Yemen.

Seeming to contradict the Western stereotypes of Muslim male dominance and oppression, in reality Yemeni women are the staunchest supporters of their traditional attire. It is seen as a symbol of maturity and self-respect and its arrival is to be welcomed. Young girls prepare for their first veil as British girls might for their future wedding-dress. Leaving wider issues of education and equality aside for the purposes of this brief discussion, the veil itself is, for Yemeni women, a cherished item. One woman compared covering her body to protecting a precious jewel, something that no one else is allowed to touch or spoil.

While Yemeni men may struggle to rationalise the veil’s place in society, women, for their part, are more likely to espouse full support. But when questioned on the accompanying limitations of the veil, they often become uncomfortable and distant, sometimes even confused. When asked whether it stops women finding work or meeting new people, reactions suggest that such thoughts had never crossed their minds. It is simply not a consideration.

espouse full support. But when questioned on the accompanying limitations of the veil, they often become uncomfortable and distant, sometimes even confused. When asked whether it stops women finding work or meeting new people, reactions suggest that such thoughts had never crossed their minds. It is simply not a consideration.

Most important for Britain and its media to keep in mind, however, is the refreshing discovery that, in Yemen, neither men nor women judge the veil against other culture’s traditions. While we in Britain consistently reduce talk of the veil to a meaningless exchange of opinion, in Yemen they seem to have accepted the counter-productivity of this long ago. Steps are being made, albeit slowly, to open up career opportunities to women in both private and state-run industries. A look at Yemen’s statute book reveals that, in theory at least, men and women have equal rights of ownership, voting and many other fundamental elements of society. Personal views on the wearing of the veil can only be truly meaningful after in depth exposure to a society where the practice is accepted as normal, not demonised as something akin to a Halloween costume. Even such informed views may not ease the existing conflicts.

It is clear, having only touched on the superficial reactions of Yemenis to their beloved yet contentious tradition, that a simplification of the issue would immediately invalidate any subsequent argument. Exploration into what place the veil has in our own secular and individualistic society should continue but must do so unhindered by vacuous media scandalising and uninformed judgment. Only if focus is realigned to tolerance and acceptance rather than judgemental subjectivity, will we find ourselves enlightened along the way, not having to stumble through confused and repetitive debates. Perhaps if we take our lead from Yemenis and remove self-centred opinion from the debate entirely, prejudice would loosen its grip and any worsening of inter-cultural relations would finally come to a halt.

JESS McCONNELL is a student of Arabic at the University of Edinburgh. She has worked for the Yemeni Times and lived in the Gulf.

Having mined every last nugget of scandal from the recent crisis surrounding Jack Straw’s comments over the veil, this country as a whole seems in desperate need of a little more understanding and basic knowledge of the subject. The controversy surrounding Mr. Straw’s views was almost purely a media creation, with newspapers eagerly taking his words out of context and busying themselves with creating sensationalist headlines.

All the while, the seeds of an important debate were ignored. Throughout the weeks that followed, print media, television and radio stations devoted unprecedented airtime to the story, yet failed to conduct a sustainable debate, much less produce a single constructive conclusion. Extreme views from both Muslims and non-Muslims made for juicy reporting. While it seemed that every man and his dog were approached for their own two cents’ worth.

This episode proved both worrying and frustrating. The extent of this country’s ignorance and prejudice has been revealed and is truly astounding. Of the countless opinions put forward, almost all were mis- or entirely uninformed. The situation was exacerbated by the fact that hardly a single article or programme gave time to a factual exploration of the history behind the veil or the reality of its position in the Islamic faith today.

This is not to say that we should all be experts or that one must be an expert before discussing the topic. Rather, that the lack of effort in seeking better understanding, instead of provoking a highly-charged and overly subjective debate, was shameful.

Perhaps this imbalance could be partially addressed by focusing here on a particular

country in the Middle East. Yemen is a nation where veil-wearing is as big a part of life as going to work or having breakfast. It is one of the few remaining Islamic states where close to 1oo% of women wear the niqab - the veil covering the whole body except for the eyes. A large proportion of older women wear black gloves as well, and in more isolated rural areas women often cover their eyes with a thin black mesh. While this custom is normal for Yemenis, it is certainly not without controversy of its own. Yemenis, for the most part, are happy to discuss the veil but rarely will two people, male or female, express the same opinion. Reasons for its dominance seem few and far between, with even the most traditional Yemenis often unable to account for its popular resurgence in recent decades.

country in the Middle East. Yemen is a nation where veil-wearing is as big a part of life as going to work or having breakfast. It is one of the few remaining Islamic states where close to 1oo% of women wear the niqab - the veil covering the whole body except for the eyes. A large proportion of older women wear black gloves as well, and in more isolated rural areas women often cover their eyes with a thin black mesh. While this custom is normal for Yemenis, it is certainly not without controversy of its own. Yemenis, for the most part, are happy to discuss the veil but rarely will two people, male or female, express the same opinion. Reasons for its dominance seem few and far between, with even the most traditional Yemenis often unable to account for its popular resurgence in recent decades.Early last century, the veil was much less prevalent in the country and women often wore no headscarf at all. No doubt the British presence in Aden helped to foster a more liberal and more secular culture, the absence of which, since 197o, is a sign of Yemenis actively reclaiming their Islamic heritage. However, older men and women will occasionally reminisce fondly about times gone by, when there was less of a divide between the sexes, and freely admit that life has since become more difficult. In short, although the niqab is held as an important symbol of modesty and protection for today’s Yemenis, few see it as entirely positive.

Often, when speaking to Yemeni men, a clear divide is detectable between what they say in general terms and any references to their own families. Ideally, yes, the veil would be less of an unresolved issue, but realistically, to abandon it would be unthinkable.

A Yemeni, whom I met while travelling in the country, told me of his experience as he tried to explain the contradictions he encounters in his own life. A religious man, who walks each morning at sunrise to his local mosque and even abstains from the national pastime of chewing the mildly intoxicating qat leaf, he was married recently to a family friend, some years his junior. They drove to Aden together, after a long and strictly traditional wedding ceremony, to spend some time alone, but when my friend suggested his new wife uncover her face in the car, she refused. Motorways do not exist in Yemen, and so their route South took them through quiet, mountain roads and maybe the odd, ramshackle village. In addition, he told me, the temperature in his old land-cruiser was almost stifling, rising even further as they travelled deeper into the desert. The story was told with a look of sadness and at times guilt. This man regards himself as entirely true to his faith and yet he feels he may have insulted his wife without even meaning to. The veil remained and my friend, having lived a traditional Yemeni life for over twenty-five years, was left with a new kind of restriction to deal with, a deeper and more affecting sort of divide.

Communities in Yemen exist within strict social boundaries, which, if crossed, can bring incalculable shame upon an entire family. Although not a small state, extended family groups are usually spread out among small villages all over the countryside. This, the result of the loyal preservation of an ancient tribal system, renders change on any level a monumental occurrence. If one relative living in Sana’a, the capital, begins to draw unusual attention, news will spread down the street, into the local area and before long out into the country, to that family’s home-village and the tribe as a whole. One person alone could not bear such pressure. The Yemeni ‘guilt-culture’ is a powerful concept that limits discussion of progression or reforms to the theoretical. So, despite rational, even regretful, debate, there is simply no room for change.

Another story thrust into the spotlight following Jack Straw’s comments was that of Aishah Azmi, a classroom assistant in West Yorkshire. This young Muslim woman wears the niqab and refused to remove it in front of male staff at the school where she worked. The attitude with which Azmi approached the question of her behaviour is mirrored in Yemen.

Seeming to contradict the Western stereotypes of Muslim male dominance and oppression, in reality Yemeni women are the staunchest supporters of their traditional attire. It is seen as a symbol of maturity and self-respect and its arrival is to be welcomed. Young girls prepare for their first veil as British girls might for their future wedding-dress. Leaving wider issues of education and equality aside for the purposes of this brief discussion, the veil itself is, for Yemeni women, a cherished item. One woman compared covering her body to protecting a precious jewel, something that no one else is allowed to touch or spoil.

While Yemeni men may struggle to rationalise the veil’s place in society, women, for their part, are more likely to

espouse full support. But when questioned on the accompanying limitations of the veil, they often become uncomfortable and distant, sometimes even confused. When asked whether it stops women finding work or meeting new people, reactions suggest that such thoughts had never crossed their minds. It is simply not a consideration.

espouse full support. But when questioned on the accompanying limitations of the veil, they often become uncomfortable and distant, sometimes even confused. When asked whether it stops women finding work or meeting new people, reactions suggest that such thoughts had never crossed their minds. It is simply not a consideration.Most important for Britain and its media to keep in mind, however, is the refreshing discovery that, in Yemen, neither men nor women judge the veil against other culture’s traditions. While we in Britain consistently reduce talk of the veil to a meaningless exchange of opinion, in Yemen they seem to have accepted the counter-productivity of this long ago. Steps are being made, albeit slowly, to open up career opportunities to women in both private and state-run industries. A look at Yemen’s statute book reveals that, in theory at least, men and women have equal rights of ownership, voting and many other fundamental elements of society. Personal views on the wearing of the veil can only be truly meaningful after in depth exposure to a society where the practice is accepted as normal, not demonised as something akin to a Halloween costume. Even such informed views may not ease the existing conflicts.

It is clear, having only touched on the superficial reactions of Yemenis to their beloved yet contentious tradition, that a simplification of the issue would immediately invalidate any subsequent argument. Exploration into what place the veil has in our own secular and individualistic society should continue but must do so unhindered by vacuous media scandalising and uninformed judgment. Only if focus is realigned to tolerance and acceptance rather than judgemental subjectivity, will we find ourselves enlightened along the way, not having to stumble through confused and repetitive debates. Perhaps if we take our lead from Yemenis and remove self-centred opinion from the debate entirely, prejudice would loosen its grip and any worsening of inter-cultural relations would finally come to a halt.

JESS McCONNELL is a student of Arabic at the University of Edinburgh. She has worked for the Yemeni Times and lived in the Gulf.

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home